Pompeii is big. Not in the modern sense of a big city, or even by the standards of ancient big cities, but in a human experiential sense. Walking the city takes time. To walk straight through Pompeii without stopping, from the entrance at the Porta Marina in the west to the Porta di Sarno at the eastern fortification, takes a full 20 mins (1,100m). But this is only one of many paths cutting through and across the city. Additionally, walking at that pace over the rutted pavements will leave you no time to look up from your feet to see the vertical scale of Pompeii either. In addition to buildings that soar to three stories above ground and those that tumble four stories down the southwestern cliffside, the ground level itself changes more than thirty meters between the Porta del Vesuvio and the Porta di Stabia. Even if a modest ancient town, scale of Pompeii is still sufficient to tire you out after only a few hours of exploring it.

Pompeii seems even bigger when you try to map that same landscape. While the Soprintendenza works hard to curate the availability of dozens of major houses in the city (to preserve our safety and interest), there are hundreds and hundreds of buildings that one will walk by without so much as a glimpse and still hundreds more in the areas closed off to tourists that can’t be seen at all. Mapping the city not only requires defining every one of those buildings, but also all the streets, sidewalks, the fortification walls and the tombs beyond them, as well as the unexcavated portions of the city. Beginning in 2013, the Pompeii Bibliography and Mapping Project took on the challenge of making the many, many maps of Pompeii – many of them good and some of them digital – available as a single online resource (and paired with a fulsome bibliography). In that work we were largely successful (see our White Paper), but had really only scratched the surface of Pompeii’s deep mapping potential. Now, with the generous support of the Getty Foundation’s Digital Art History program, we are working to increase the resolution of the map, pushing downward from every building into every room, to every wall that surrounds those rooms. This is an essential level of resolution for PALP if we are to put each mosaic on the floor of a room and each fresco on the correct wall in that room.

Map of Rooms at Pompeii

To do this required drawing a polygon for everyone of the more than 10,000 rooms in the city. Fortunately, much of this drafting work was done back in 2014 when two UMass Amherst students, Landy Joseph and Jennifer Verville, drew and labelled thousands of rooms based off of the maps published in the Pompei. Pitture e Mosaici (PPM) volumes. Their efforts, heroic as they were, could only be the first draft of the work and the inevitable missing sections, gaps, and errors all needed to be addressed by a new team of UMass students. Leading the charge to correct these data in 2019 was Stefanie Taylor, who supervised a five person team to fix these issues and identify others still not yet encountered. The basic task was for students to go building-by-building and then room-by-room across a Region of the city, comparing the shapes of these buildings and their rooms (as well as their labels) in the PBMP’s online map with the PPM’s reference maps. Doing the actual work, however, required a number of resources and further instructions as many of our students not only were new to the project, but also unfamiliar with Pompeii and its idiosyncratic systems of documentation.

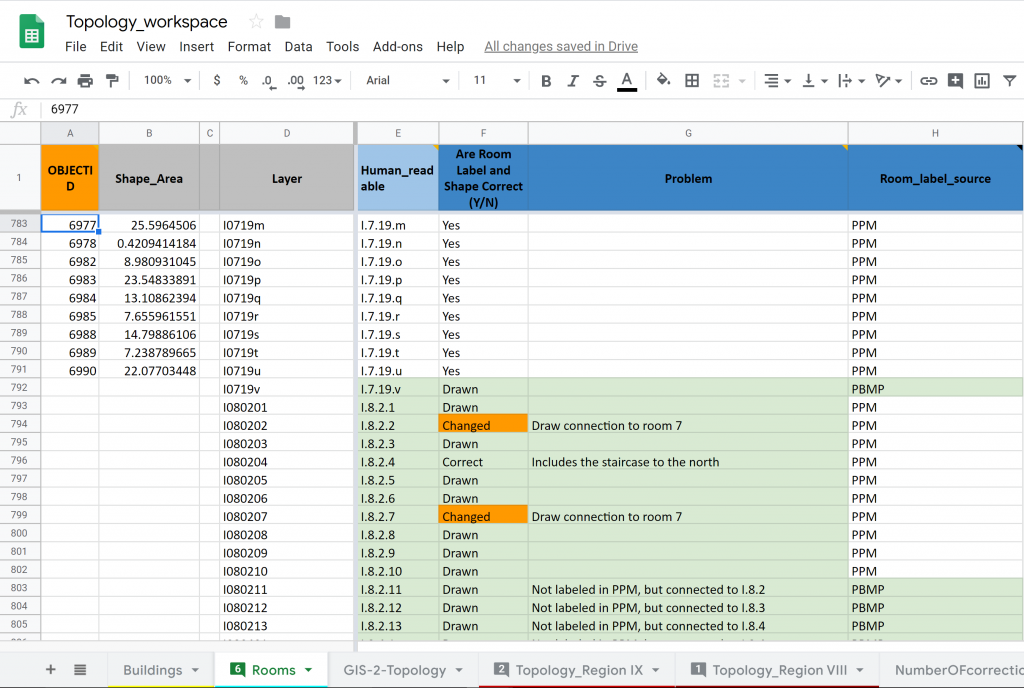

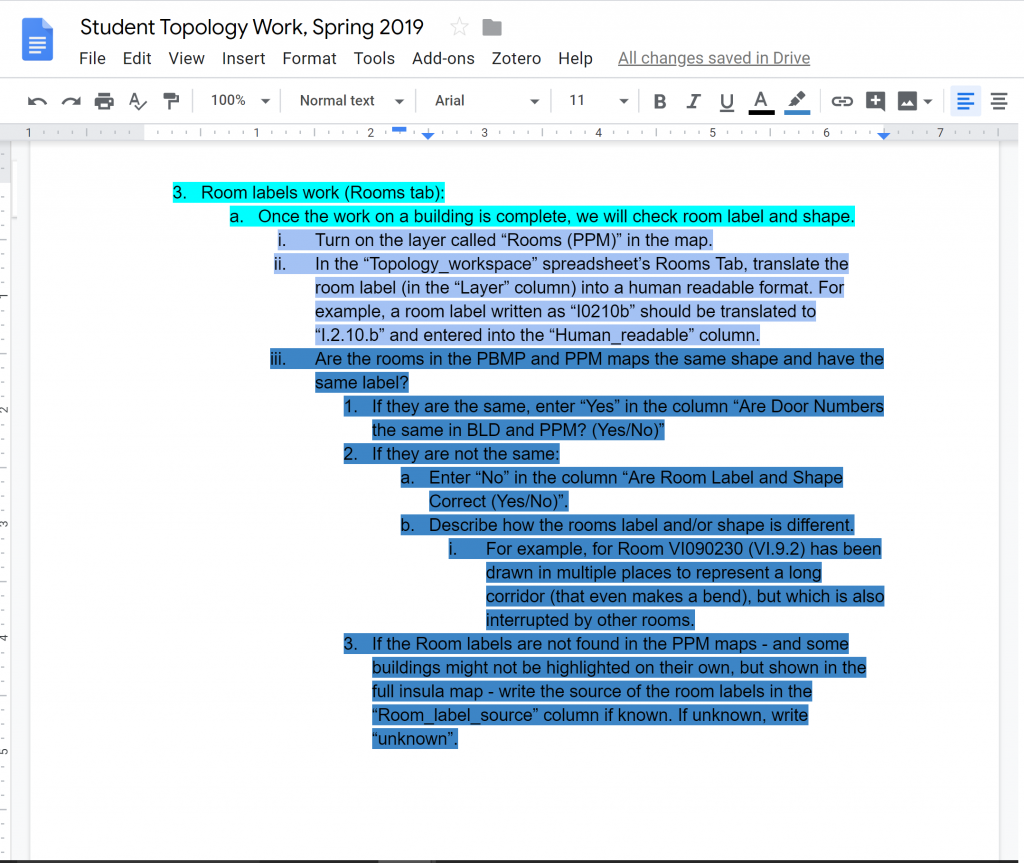

The solution we decided upon to manage the work, to accommodate the (natural) inexperience of the workforce, and to make use of the resulting data was to export the list of rooms we had drawn into a Google Sheet and build a place for the student’s assessments. We called this sheet the Topology Workspace, and in it we provided the students a place to convert the somewhat unwieldy address label (I0101a) to a more human readable format (I.1.1.a), state if the shape and/or label of the room matched in the PPM and the PBMP maps, and if not, to explain why. Accompanying this spreadsheet was a set of detailed, step-by-step instructions. To further clarify the connection between the workspace and these instructions, sections of text were highlighted in a range of colors that matched a corresponding color in the header row of the Topology Workspace. This color coding would prove to be not only effective, but also highly satisfying to me. (We will see this device used later in (at least) the workspace we use to capture our descriptions of the artworks). Over the course of the spring semester, students identified more than 2,700 potential problems with the rooms, each of which I examined and corrected in our master GIS files. Along the way, an additional task was added. Since we were already looking at every room – to note when there was a feature inside that room, such as a masonry triclinium, an impluvium or other water related features, stair, and/or commercial or industrial installations, and if so to identify it as one of these types.

At the end of this process we had a high degree of confidence in the overall shape, nomenclature, architectural features for all rooms in Pompeii. At this point, we were now ready to run some geoprocessing tools on the rooms dataset in order to enrich it and other GIS layers with more information as well as to build new datasets. For example, using the spatial relationship between the rooms, we determined programmatically how all rooms interconnect with each other and made this relationship of “is connected to” part of each room’s list of attributes. Similarly, we combined the data in the rooms and streets layers with the architecture layer to determine into which room or onto which street every wall faces. Finally, from the rooms data it was possible to generate a line at the place where two rooms intersect and represent the place of doorways, visualizing the implicit notion of their existence created by the “is connected to” attribute of the rooms.

Together, these great efforts of our students produced an enormous, rich, and “self-aware” (i.e., the walls “know” what room they are in; doorways “know” what rooms they adjoin) set of data about the rooms, walls, and doorways across the entire ancient city of Pompeii. These data and the explicit representations of their relationships are essential to the future functioning of the Pompeii Artistic Landscape Project. Because we want to be able to make every artwork discoverable in its most specific location, we need to place a specific artwork in a particular room or on a specific wall. That means the artwork needs to be placed within a complete hierarchy of space that extends upward from a wall to a room to a building to an insula to a region and, finally, to Pompeii itself. Our efforts in the first months of PALP have successfully built this deeper spatial resolution and permitted us to turn our focus to building a new workspace in which students can describe the artworks and not only the rooms they might belong in.

Still, there is more work to do on PALP’s map of Pompeii, including devising layers that can make clear the rooms and spaces that exist above the ground floor level and those below ground as well. There also remains a very large number of very tiny gaps and overlaps among the features in the GIS – inconsequential, but annoying topological errors – that need to be eliminated. With the help of Dr. Rebecca Seifried, the UMass GIS librarian, we’ve begun to identify those errors and will soon correct them. More importantly, Dr. Seifried has build a wonderfully complex GIS model that will add information to each wall and which may prove very interesting in later Art Historical analyses using PALP. Specifically, she has invented a method for every wall in a room to “know” what other walls it faces across a room, allowing a future user of PALP to ask which artworks might be in direct visual dialog with one another. As these improvements in spatial consistency and enrichments in spatial awareness are completed, they will be added not only to the underlying data for PALP’s spatial hierarchy, but also will be shared via the PBMP’s public online mapping interface.